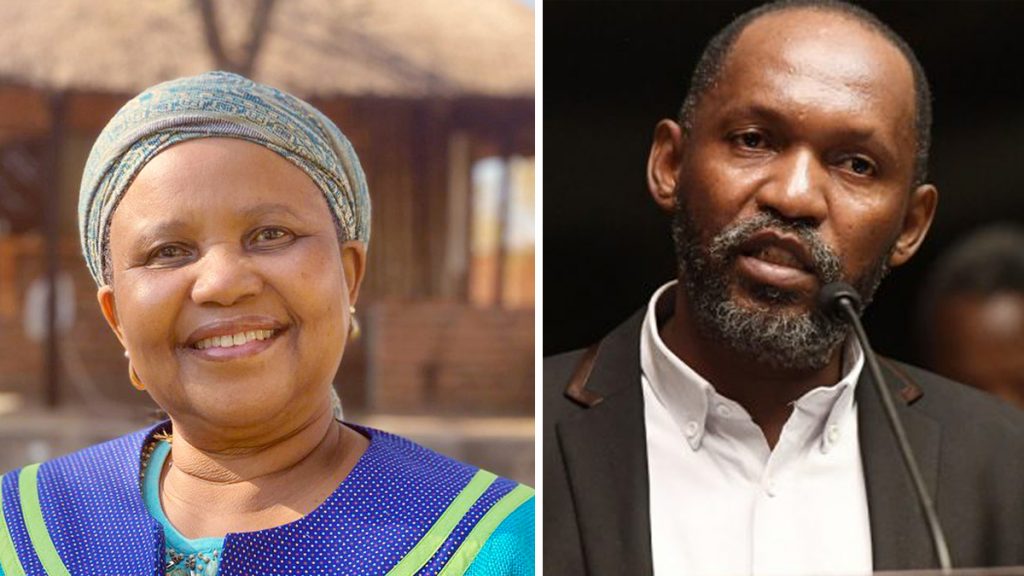

* Gaontebale Mogosi

The fuzzy or ambiguous claims of the BDP state to appropriate the Forest Hill Farm of Ba–Ga–Malete has attracted the attention of Real Alternative Party on the land question in Botswana. As a socialist revolutionary party anchored on politics of African communal democracy, it would be amiss on RAP not to indulge on the Ba–Ga–Malete land contestation by the BDP State as our revolutionary political agenda prioritizes land rights and claims. We are a party which is committed to social justice and as such opposed to state-sponsored land grabbing.

The land contestation by BDP Government over Ba-Ga-Malete Forest Hill Farm raises some pertinent albeit critical questions about the efficacy of the land question in dealing with questions of transitional justice, and development. The battle between BDP government and Ba–Ga–Malete tribal authority reveals the ability of the ruling elites to overcome even moderate local autonomy. The emphasis by BDP government to take over land of Ba–Ga–Malete serves to undermine simple, economistic premises about the security of rural economies and the need for diversification of income strategies to complement government in the way of collective goods to citizens. The push to ransack Ba-Ga-Malete of Forest Hill Farm is reinforced by motifs of phony encroachment and lust at the behest of adversarial bourgeois rationalism and leisure class.

Rather than respect the integral connection between Ba-Ga-Malete survival and biodiversity, the BDP State is obdurate to usurp Ba-Ga-Malete of Forest Hill Farm as resource for capital. Despite the rhetoric by Kgosi Mosadi Seboko that Forest Hill Farm was obtained by way of tittle – right and that it represents a continuos trusteeship or guardianship (‘for the living and the yet-to-be-born’) of her tribe, the BDP government has decided to thwart such tenure security and chooses to stubbornly undermine the ability of Ba–Ga–Malete to obtain a livelihood from such land. We find it hypocrite of a democratically elected government to view native citizens as obstacles rather than agents of their own development.

Majority of Land Neighbouring Forest Hill is owned by a minority few:

What aggravates is that the BDP State finds it absolutely good that the minority of people who are the (descendants of the colonisers/ invaders and their acolytes) still own the majority of land through title deeds, while on the other hand it has become very relentless to strip Ba-Ga-Malete of a very tiny piece of land who nevertheless managed to acquire it through a legally sanctioned land tenure procedure; tittle deed. A paltry few of European, Asian, together with their national petty national bourgeois and the colonial churches is part of the minority that owns vast pieces of arable land in the South East District along the Notwane river corridor forest, whilst majority of the population in South East District live in poverty. The dispossession of Ba-Ga-Malete of Forest Hill Farm who already have very skewed land in their possession will be to undermine their ability to obtain a livelihood from such landed resources. It will be to impose new burdens on Balete whose history of land alienation because of white settler conquest and subjugation has created structural inequities of ownership patterns against Balete. The creation of fenced ranches within the South East District by the British colonists has, effectively reduced the amount of land available and has made it impossible for Balete to expand their territory more so that their tiny district borders the north – west province (former Transvaal) of South Africa.

The failure of the government to reverse skewed ownership patterns coupled with the persistence of human rights abuses suffered by farm workers and labor tenants in the Kgale – Mokolodi – Notwane terrain is testimony to a BDP`s failed Democratic rule. The BDP Government has proven to be incapable to address the historical imbalances that British colonialism brought upon indigenous people and has failed to do fair and equitable land redistributions so that Batswana could have access to their birth right inheritance from their Creator and their ancestors. And it is because the BDP interpretive political framework of access to and use of land is the reproduction of privilege and the preserve of colonial ‘extroversion’ at the cost of its native citizens.

BDP State has a coercive capacity of its predecessor [the British colonial state]:

The assault on Ba-Ga-Malete`s land has a much longer history than of most native communities of Botswana. In fact it is the same as of North East District where the Tati Company led to the eviction of local communities to give way to farms for settler farmers. Similar evictions and relocations took place in the Tuli Block and Gantsi Block Farms where John Cecil Rhodes’ British South African Company was active in settling European farming communities.

The arable pastures of the kgale – Notwane represent a continuous ecological zone exploited by the colonists and their descendants, from the time of Bechunaland Protectorate up to now, who did not recognize the territory occupied by Ba-Ga-Malete tribe prior to arrival of British conquerors. Since rivers are important for fisheries as well as for riverine gardens, and riverbeds are also a source for the gravel and sand used in the increased construction associated with growth in urban and peri-urban areas, the foreign conquerors annexed the Notwane-Mokolodi forest terrain for exploitation of these lucrative resources including abundance of wildlife found in that area. The access to land for Ba-Ga-Malete in Botswana has been problematic since the advent of colonisation. The colonists had a devastating effect on Balete and Batlokwa. British colonizers displaced Balete and Batlokwa from Gaborone to Lobatse to make way for European settlers under the pretext that it served as a north – south corridor for cattle – beef economic zone. The British colonial invaded this part of land and declared it as “crown Lands” for the use of the British South African Company in 1905. According to historical records “If cattle of Balete and Batlokwa wandered onto a white farm, they were seized and held until the owner “bought” them back at above market value, as a fine or paid the value with his labour.”(The Birth of Botswana – a History of the Bechunaland Protectorate from 1910-1966, Fred Morton and Jeff Ramsay).

The relative autonomy of Ba-Ga-Malete over their piece of land here shows us that the British colonial government has had profound effects on both the BDP system of rule and the conditions under which customary and other claims and rights are defined and fought over, and on the framing of those claims and rights. Despite having (Ba-Ga-Malete) thwarted state motifs through juridical processes, BDP government displays attitude of the British colonial invaders of relentless determination to dispossess Ba-Ga-Malete of forest hill piece of land, whilst it frequently provide the means for considerable appropriation of land by a small elite. The BDP State attitude towards Ba-Ga-Malete represents a process of “internal colonization”. Sara Berry’s quote could not be more right when she concluded that clearly, the postcolonial governments ‘have joined the ranks of the exploiters’.

The Botswana Land Policy gives inordinate power to a few over the land rights of many:

The Land policy activities of BDP government are premised on ideas of “inconclusive encounters” characterized by disruption rather than transformation, intrusion rather than hegemony. Botswana`s land tenure reform is often to loosen, not strengthen local land ties by vitiating local rights of occupancy and use. Land held under customary rights is vulnerable to more direct appropriation by the state, which often acts as ultimate conservator of the nation’s soil. The BDP State Legislated the Tribal Land Act as a weapon in the armoury of government to weaken and oppress tribal communities. The act is being applied to veil a greedy and patronizing ethos. The Tribal Grazing Land Act gives inordinate power to a few over the land rights of many as individual and commercial ranches have been established to give tenure security to the richer and more influential members of the communities. According to Pauline E. Peters, the increased skewing in access to valuable grazing land in Botswana occurred through the interaction between increasing commodification of livestock and state-led programmes enabling better-off and politically well-connected cattle owners to obtain highly valued and valuable boreholes (deep wells) that, in turn, facilitated improved access to a larger area of dry-land grazing (Peters 1984, 1994, Dividing the Commons: Politics, Policy, and Culture in Botswana. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press). The Tribal Grazing Land Policy has been used by the BDP ruling elites to allocate roughly 45 347 km2 or 8% of Botswana’s land mass to individuals for ranching purposes.

The ability of elites at national and local levels to gain preferential access to material and symbolic resources remains critical in Botswana. The Land Use Decree privileges and enhances the common class and political interests of the managerial bourgeoisie’ at the expense of ‘the rural and urban labouring classes. Systems of landholding and land use in Botswana reveal processes of exclusion, deepening social divisions and class formation. While a small minority has been able to intensify production and/or have obtained more land in order to be able to compete in more constrained regional and global markets, the majority of rural families have seen their options and living standards constrict, and have been forced to diversify their income strategies (mostly in the ‘informal’ sector), and some being squeezed ever more tightly in dependent patron–client relations within villages as well as with outsiders (such as owners of ranches, traders or politicians). As a result, we are witnessing frequently exacerbated conflicts and patterns of unequal access to land based on political connections and other powerful preferential interests. Reports of Land boards facilitating practices of bribing, fraudulent titling and expropriation of land has also worsened the matters around land.

All these misfortunes have much to do with colonial structures, which BDP instead of having to do away with has maintained them insofar as this enabled them to stay in power and to privilege a small – elite of politicians and civil servants under the pretext about necessary trajectories of growth and modernization based ultimately on Western European experience. This has caused Botswana with its land tenure system to dismally fail to achieve the expected results of improving agricultural investment and productivity, and instead encouraged speculation in land by outsiders, thus displacing the very people – the local users of the land – who were supposed to acquire increased land security to promote economic growth, encourage more sustainable management, and reduce poverty.

The patterns of access to and use of land needs to be a question rather than a conclusion:

The real conversion challenge lies in the Monopoly control of land. This requires a theoretical move away from privileging contingency, to one that is able to identify those situations and processes which reveal processes of exclusion, deepening social divisions and class formation. Cases of ambiguous and indeterminate outcomes among claimants over land and the instances of intensifying conflict over land, deepening social rifts and expropriation of land beg for closer attention. Apart from colonial land dispossession, land reform in Botswana has become a process that ultimately generates an internal logic of control, economic power and disempowerment from those unable to partake in the mechanisms established for land redistribution. The latent function of Botswana`s land policy represents the interest of the political elites that prevail over the manifest function because of the highly asymmetrical relations of power between the elite and the peasantry.

Therefore and in essence, the discourse around land question in Botswana must be imbued with a sentiment of land rights to redress the historical experience of land dispossession. The aim must be to restructure the skewed land ownership patterns created by both the colonial regime and the BDP State. The BDP State must” deal more effectively, and decisively with the land question of re-appropriation and redistribution. Land question in Botswana must aim at balancing the interests of the landowners with those of the land-deprived majority of its population. More emphasis needs to be placed by analysis on who benefits and who loses from instances of ‘negotiability’ in access to land, an analysis that, in turn, needs to be situated in broader political economic and social changes taking place. Issues around land in Botswana must be motivated by the BDP state’s dismal failure in dealing with the problem of land reform against the background of a land dispossession experience that spans over hundred years!

Brother Chairman

Gaontebale Mogosi

Real Alternative Party