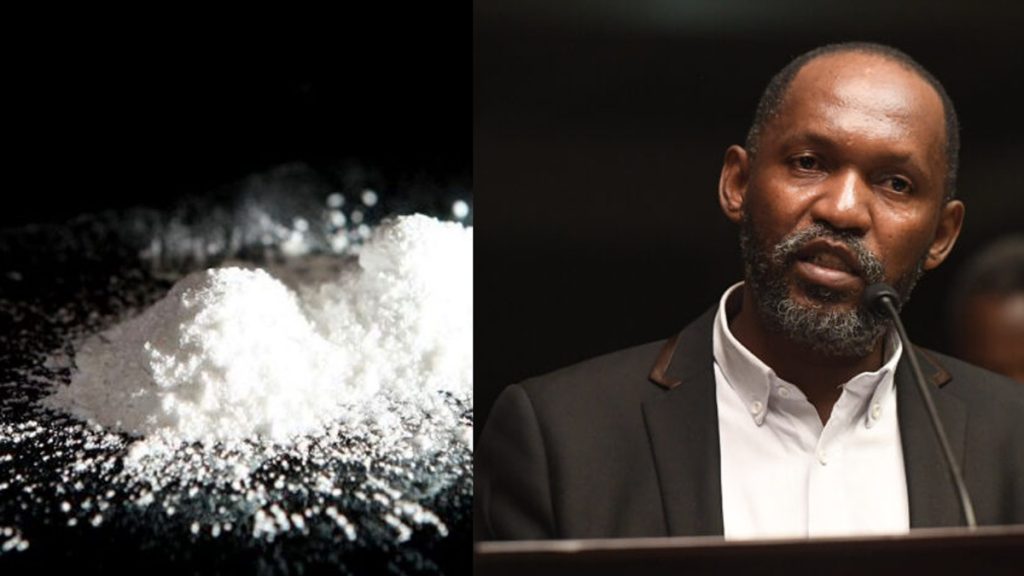

Brother Gaontebale Mokgosi

This article serves to decry the low bar set by Botswana Members of Parliament but also demonstrate their true shortfall for problem solving. Whilst I am an “outsider” and therefore cannot measure the Botswana legislative performance of an assembly with clinical accuracy, my aim is to seek to define and measure the strength and weakness of Botswana various modes of legislative–executive relations. Accordingly, this article proceeds from the outcome of the Maun court case in which Judge NthomiwaNthomiwa has adjudicated that there is no law that criminalizes possession of Methcathinone (“Cat”) in Botswana as it has not been listed in the Botswana schedule of the illicit Traffic in the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act as such.

Such a gap in the law is unfortunate considering that the pattern of Botswana parliamentary system of government has a trend of executive dominance. The executive enjoys the informational advantages so that it is so trifling that we are having an absence of proper, clear, classification of Methcathinone (“Cat”) in the schedule of the illicit Traffic in the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act. Most legislation is introduced by the Ministry, and in this manner one would presume that careful preliminary study of bills and a double deliberation in Council of Ministers and in Parliament is secured. Moreover, over the past four years, epidemiological networks on drug use in countries of the SADC region, as well as the continental Pan African Network on Drug Use (PAENDU) of the African Union, have been raising concern over growing illicit drugs and non-medical use of prescription drugs, and the growing use of New Psychoactive Substances (NPS), such as synthetic cannabinoids, cathinones and opioids. Botswana is not spared from the growing surge in illegal – drug production, trafficking and use in the SADC Region.

This trend has accelerated with the growing perception that drug abuse is not merely a crime but, on the demand side, an illness requiring treatment and, on the supply side, an industry requiring effective safeguards. The 1994 Drugs and Development report (Number 1) highlights that once established in the legitimate domestic economy, drug traffickers generally have considerable freedom: (a) to transport illicit goods under the guise of legal merchandise; (b) to create new markets for wholesale or retail distribution; (c) to establish or arrange for new sources of precursor chemicals; and (d) to launder even more illicit revenues. With the trend towards privatization, the real danger comes from the ability of drug traffickers not only to launder funds, but also to acquire portions of what constitutes a second-hand sale of global proportions.

The report further states that that precise targeting by Latin American and Asian drug cartels, as well as the extensive availability of small-scale entrepreneurs amenable to illegal pursuits, have contributed to Africa’s emergence as a trafficking heartland. Widespread use of African countries for trafficking has also led to the inevitable spillover effect of rising consumption. In particular, there has been a rise in the illicit consumption of hard drugs, in addition to the already commonplace abuse of psychotropic substances like methcathinone (“Cat”).In many respects, the cartels and entrepreneurs are simply exploiting the increasingly desperate need for revenue.

The report also shows that illicit drugs do not emerge on local markets solely because of the innovation of local entrepreneurs; rather, they are systematically introduced and marketed by traffickers who are attracted by the following: (a) a country’s general lack of legal and institutional controls; (b) geostrategic considerations; (c) government unfamiliarity with or indifference to the drug threat; and (d) prevalent economic vulnerabilities. In light of this, there is need for entrenching law enforcement mandates and capabilities in democratic foundations shaped by the collective will of the people. The development agencies can contribute to an array of initiatives in such areas as institution-building, legislative assistance and the strengthening of prevention and rehabilitation capabilities at the country level. In short, there is untapped potential for a greater operational interplay between drug control and development bodies.

The problem is the debate is still dominated by an “us” versus “them” adversarial principles especially from the side of government. Yet the drug problem cannot be adequately addressed when seen from an exclusively bipolar spectrum of perspective. In any joint undertaking between drug control and development bodies, it is essential that multidisciplinary teamwork and consultation play a crucial part. The debate must be expanded to include still other areas of social, economic, and political analysis. One of the emerging issues is increasing political intervention in senior public service appointment processes. Another issue is organizational amnesia where public sector ‘reform’ has become the goal, rather than the means for the government. Once upon a time we used to have public servants who had real content knowledge in the policy area they worked. Once upon a time, senior public servants rose up through the ranks, and had experience about what worked, and what did not work in the field.Because during the last couple of years the public service in Botswana has been constantly restructured, increasingly politicized, the technocracy is no longer good at its organizational memory. The new appointees have no idea what had gone on before and have to start all over again. And so given the increasing high turnover of senior staff we have a situation of ‘stop-go’ policy making and reinventing the wheel.

Another concern is that existence of House of Chiefs which acts as a lower legislative house to assist government in executive responsibilities including advice, is not premised on theory of the check of one house upon the other, as it is often times frequently disregarded by the cabinet to avoid responsibility or the tedium of close investigation by passing doubtful or ill-considered measures on to the cabinet by the House of Chiefs. This makes the House of Chiefs to be bereft of a political advantage. For instance, parliament seldom secures the careful consideration of any of the motions put forward for legislative consideration from the sessions of the House of Chiefs chamber. Also government sometimes seems to be deaf, or they do not really want to listen to advice even if it is tendered. Sometimes this deafness is selective. Government too often appears to have made up its mind before acting. Advice seems superfluous or if sought at all is only used to bolster particular courses of action.In such an environment it is increasingly difficult for alternative view-points to get up through the system.

Short-termism in thinking about policy issues further undermines effective policy advice. The Government is very focused on one thing: getting re-elected, maximising votes, and doing what they have to do to get over the line at the next election. It is extraordinary how this not just focuses their attention, but monopolizes their thinking It is made worse at the Legislative body level! The Botswana parliament is just a ‘legitimizing assembly’, in which legislatures serve as merely a debating or ratifying body of the executive branch of government. Although the core perspective of legislatures has to do with making law, however there is tenuously the absence of clear indicators for the systematic measurement of their legislative power. The present – day parliament is more party-oriented. The force of partisanship has strengthened bias representation and its corollary parochialism continues to dominate parliamentary electoral politics. Seniority is no longer the sole criterion in selecting committee chairs and the major party is the pre-eminent political actor in the parliamentary committees. This arrangement has made Parliament to find it easier to represent than make laws. It has also led to a problem owing to mutual distrust of oversight by the executive in parliament. Alternatively, parliament has become vehicle for partisan attacks that rely on an inconsistent application of ethical rules across different parties.

In terms of policy-making power, Botswana legislatures (across party-line), can be classified as generally “reactive” as opposed to “proactive”. Far from an exemplar of a strong policy-making legislature, the Botswana Parliament is strikingly unable to exercise constructive, as opposed to obstructive legislative power. It is now ‘a policy obstructing legislature par excellence’. Even when all parties recognize a problem’s optimal solution, one party’s leadership may decide to block legislation because it can’t afford to grant the other a political victory. Ongoing partisan activity in parliament often amounts to a tremendous waste of time, which is spent not on articulating principled policy and values but instead on posturing, vilifying opponents and grandstanding on behalf of themselves, their parties, or their preferred cause and advertising. Precious little of this discourse contributes to genuine public deliberation, whereby voters might learn more than the partisan leanings of the candidates on offer.

One other factor contributing to legislative failure is elections, particularly national ones as they too often attract the wrong kind of candidates. There is a problem of some people aspiring for political office simply because of the salary on offer, rather than out of any desire to participate in good faith i.e. those who view the political job as an easy pay – check. As a result the Botswana Electoral system produces political officials who also have substantial knowledge deficits, exacerbated by ideological commitments that include rigid (and often grossly incorrect) convictions about government, society, and the natural world. This kind of reasoning encourages the dangerous inference that legislation may be an individual or personal function. It produces a demoralization of the legislative session in which anything is possible, and frames a spectacle which destroys confidence in politics as a development arena.

Given the absence of such deliberation, it is no surprise that legislators cannot ensure the public legitimacy of the chamber they occupy. This seems to lie at the heart of the issues concerning the recent court pronouncement on “cat” – (a psychotropic substance illicitly consumed in developing countries often and originating in industrialized countries). Everyone knows, it seems, about the increased supply of methcathinone (“Cat”) by sluggard and irresponsible adults to children, adolescents and youth in Botswana for their inhalant and intoxication in exchange for quick money, except the legislative arm of government. And it is precisely, because the government sometimes seems not to learn from previous mistakes. This is a real problem in the political administration advisory game, and partly explains why every metric of trust in government, is at or near an all-time low.

But what is needed, is sincerity and virtue to restore vitality and dignity to the legislative branch, constituting it upon practical and not theoretical lines, and raising it to a position of constant and active participation in the government of the state. Although a unicameral legislature i.e constituted of a single chamber, Botswana might as well adopt an institution which has proved its value in several countries (e.g. Belgium, Mexico), and is known as the “permanent deputation” or the “permanent commission.” The uses of such a body in Botswana might be several. Chosen before the adjournment of each session by the legislature out of its own members, and composed of a number of men with the qualifications and the leisure to give continuous attention to the affairs of the state, such a standing commission might be a permanent committee upon legislation, reviewing the action of the legislature at its past session and anticipating its action during the coming session.

It might reconsider projects of law left un-enacted, and examine new projects sent in by members of the legislature for future consideration. The legislature might well accord to this deputation an unlimited prerogative of introducing at the opening of the parliament session new bills, while at the same time restricting to a minimum the number of bills which a private member might introduce other than through the permanent commission. This would be one practicable way of limiting the unbridled license which overwhelms our legislature with projects of law, and which has been sufficiently commented upon. To it might also well be entrusted a considerable ordinance power, the power to frame subordinate legislation consistent with statutes of the legislature and designed to carry out the provisions of these statutes, which, upon receiving the approval of the parliament and signing by the president, would have the force of law. This would relieve our laws of the immense mass of details which encumber them and would also reduce the erroneous omissions in specific laws as it is the case with the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act. In this view, such a system “would prevent the formation of self-serving and self-perpetuating political classes disconnected from their electorates.